Long thoracic nerve injuries: new theories to consider

The long thoracic nerve supplies the Serratus anterior, whose root value is (C5-C7) but the root from C7 may be absent.

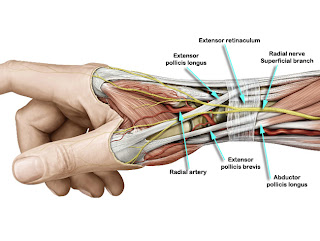

Anatomic path: The roots from C5 and C6 pierce the Scalenus medius, while the C7 root passes in front of the muscle. The nerve descends behind the brachial plexus and the axillary vessels, resting on the outer surface of the Serratus anterior. It extends along the side of the thorax to the lower border of that muscle, supplying filaments to each of its digitations (finger-like projections).

Long thoracic nerve injuries in sports: Due to its long, relatively superficial course, it is susceptible to injury either through direct trauma or stretch. Injury has been reported in almost all sports, typically occurring from a blow to the ribs underneath an outstretched arm.

Also injuries to the nerve can result from carrying heavy bags over the shoulder for a prolonged time. Symptoms are often minimal – if symptomatic, a posterior shoulder or scapular burning type of pain may be reported.

A lesion of the nerve paralyses the serratus anterior to produce scapula winging, which is most prominent when the arm is lifted forward or when the patient pushes the outstretched arm against a wall. However, even winging may not be evident until the trapezius stretches enough to reveal an injury several weeks prior.

Long thoracic nerve palsy from a possible dynamic fascial sling cause:

Following is an review by Hester P et al

Long thoracic nerve palsy can result from sudden or repetitive external biomechanical forces. This investigation describes a possible dynamic cause from internal forces.

Six fresh cadaveric shoulders (3 female, 3 male, 4 left, 2 right) with full range of motion were systematically dissected to evaluate the anatomic course of the long thoracic nerve. In all specimens a tight fascial band of tissue arose from the inferior aspect of the brachial plexus, extended just superior to the middle scalene muscle insertion on the first rib, and presented a digitation that extended to the proximal aspect of the serratus anterior muscle.`

With progressive manual abduction and external rotation, the long thoracic nerve was found to "bow-string" across the fascial band. Medial and upward migration of the superior most aspect of the scapula was found to further compress the long thoracic nerve. Previous investigations have reported that nerves tolerate a 10% increase in their resting length before a stretch-induced neuropraxia develops. Previous studies postulated that long thoracic nerve palsy resulted from the tethering effect of the scalenus medius muscle as it actively or passively compressed the nerve; however, similar neuromuscular relationships occur in many other anatomic sites without ill effect.

We propose that the cause of long thoracic nerve palsy may be this "bow-stringing" phenomenon of the nerve across this tight fascial band. This condition may be further exacerbated with medial and upward migration of the superior aspect of the scapula as is commonly seen with scapulothoracic dyskinesia and fatigue of the scapular stabilizers. Rehabilitation for long thoracic nerve palsy may therefore benefit from special attention to scapulothoracic muscle stabilization.

References:

Hester P et al; J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2000 Jan-Feb;9(1):31-5.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Long_thoracic_nerve

Anatomic path: The roots from C5 and C6 pierce the Scalenus medius, while the C7 root passes in front of the muscle. The nerve descends behind the brachial plexus and the axillary vessels, resting on the outer surface of the Serratus anterior. It extends along the side of the thorax to the lower border of that muscle, supplying filaments to each of its digitations (finger-like projections).

Long thoracic nerve injuries in sports: Due to its long, relatively superficial course, it is susceptible to injury either through direct trauma or stretch. Injury has been reported in almost all sports, typically occurring from a blow to the ribs underneath an outstretched arm.

Also injuries to the nerve can result from carrying heavy bags over the shoulder for a prolonged time. Symptoms are often minimal – if symptomatic, a posterior shoulder or scapular burning type of pain may be reported.

A lesion of the nerve paralyses the serratus anterior to produce scapula winging, which is most prominent when the arm is lifted forward or when the patient pushes the outstretched arm against a wall. However, even winging may not be evident until the trapezius stretches enough to reveal an injury several weeks prior.

Long thoracic nerve palsy from a possible dynamic fascial sling cause:

Following is an review by Hester P et al

Long thoracic nerve palsy can result from sudden or repetitive external biomechanical forces. This investigation describes a possible dynamic cause from internal forces.

Six fresh cadaveric shoulders (3 female, 3 male, 4 left, 2 right) with full range of motion were systematically dissected to evaluate the anatomic course of the long thoracic nerve. In all specimens a tight fascial band of tissue arose from the inferior aspect of the brachial plexus, extended just superior to the middle scalene muscle insertion on the first rib, and presented a digitation that extended to the proximal aspect of the serratus anterior muscle.`

With progressive manual abduction and external rotation, the long thoracic nerve was found to "bow-string" across the fascial band. Medial and upward migration of the superior most aspect of the scapula was found to further compress the long thoracic nerve. Previous investigations have reported that nerves tolerate a 10% increase in their resting length before a stretch-induced neuropraxia develops. Previous studies postulated that long thoracic nerve palsy resulted from the tethering effect of the scalenus medius muscle as it actively or passively compressed the nerve; however, similar neuromuscular relationships occur in many other anatomic sites without ill effect.

We propose that the cause of long thoracic nerve palsy may be this "bow-stringing" phenomenon of the nerve across this tight fascial band. This condition may be further exacerbated with medial and upward migration of the superior aspect of the scapula as is commonly seen with scapulothoracic dyskinesia and fatigue of the scapular stabilizers. Rehabilitation for long thoracic nerve palsy may therefore benefit from special attention to scapulothoracic muscle stabilization.

References:

Hester P et al; J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2000 Jan-Feb;9(1):31-5.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Long_thoracic_nerve

thanks a lot for this great information

ReplyDeletephysical therapy and rehabilitation protocols

http://physiophysio.blogspot.com/

Thanks

ReplyDeleteMichael & jerometnewman for your encouraging words. i will try to keep the scientific community updated as far as possible.

thanks again

satyajit

physioindia