Understanding fascia dynamics through activity of myofibroblasts

The myofibroblasts: Myofibroblasts in fascia are connective tissue cells with smooth muscle-like contractile capacities. Originally discovered in the 1970’s, these cells are now known to play a major role in wound healing, tissue fibrosis, and pathological fascial contractures.

Their evolution–usually seen as from regular fibroblasts to proto-myofibroblasts, to fully differentiated myofibroblasts, to final apoptosis–is influenced by mechanical tension, cytokines, and specific proteins from the extracellular matrix. Given its relatively recent discovery, many questions still exist about this new cell type.

Biology of this cell, the interactions with its environment, and its presence and role in collagenous connective tissues are a matter of research & great debate.

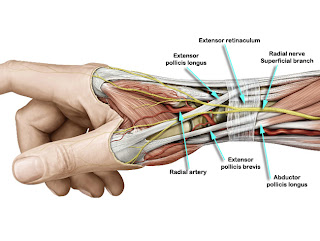

Capability Of Mechanotransduction Of Fascia: The various viscoelastic tissue that constitute fascia (ligaments, tendons, capsules, discs, etc.) are also sensory organs. Various types of receptors capable of monitoring tension, elongation, pressure, velocity, pain, etc are located in such tissues and create a neurological feedback mechanism by which reflexive interaction with muscles is provided to maintain joint stability and safety as well as coordination of movement.

Density and stiffness of fascial sheets is regulated by connective tissue cells, which are responsive to mechanical stimulation, genetic factors, and chemical messengers. A wide spectrum of fascial tonicity expressions exists. On one end of the spectrum are chronic tissue contractures like palmar fibromatosis (Morbus Dupuytren), hypertropic scar, or frozen shoulder, which are associated with an increased fascial stiffness and a high density of contractile cells. Similar contractile cells, although in much lesser density, have also been found in fascial tissues of normal patients. On the other end of the spectrum are patients with chronic hypermobility, as they usually express hyperextensibility of the skin and delayed wound healing. This session will look at the interactions between active cellular contraction and chronic fascial contractures, and how their interactions may be involved in fascial stiffness adaptations.

Fascia is a tissue whose composition and material properties are constantly evolving in response to its changing mechanical environment. Mechanotransduction, or the ability of cells within fascia to perceive and respond to mechanical forces, is a key mechanism responsible for this fascia “remodeling”. Disruption of the fascia due to injury or overuse also results in corrupted feedback signals and neurological disorders that are exposing the tissue to additional potential for injury or movement disorders.

Their evolution–usually seen as from regular fibroblasts to proto-myofibroblasts, to fully differentiated myofibroblasts, to final apoptosis–is influenced by mechanical tension, cytokines, and specific proteins from the extracellular matrix. Given its relatively recent discovery, many questions still exist about this new cell type.

Biology of this cell, the interactions with its environment, and its presence and role in collagenous connective tissues are a matter of research & great debate.

Capability Of Mechanotransduction Of Fascia: The various viscoelastic tissue that constitute fascia (ligaments, tendons, capsules, discs, etc.) are also sensory organs. Various types of receptors capable of monitoring tension, elongation, pressure, velocity, pain, etc are located in such tissues and create a neurological feedback mechanism by which reflexive interaction with muscles is provided to maintain joint stability and safety as well as coordination of movement.

Density and stiffness of fascial sheets is regulated by connective tissue cells, which are responsive to mechanical stimulation, genetic factors, and chemical messengers. A wide spectrum of fascial tonicity expressions exists. On one end of the spectrum are chronic tissue contractures like palmar fibromatosis (Morbus Dupuytren), hypertropic scar, or frozen shoulder, which are associated with an increased fascial stiffness and a high density of contractile cells. Similar contractile cells, although in much lesser density, have also been found in fascial tissues of normal patients. On the other end of the spectrum are patients with chronic hypermobility, as they usually express hyperextensibility of the skin and delayed wound healing. This session will look at the interactions between active cellular contraction and chronic fascial contractures, and how their interactions may be involved in fascial stiffness adaptations.

Fascia is a tissue whose composition and material properties are constantly evolving in response to its changing mechanical environment. Mechanotransduction, or the ability of cells within fascia to perceive and respond to mechanical forces, is a key mechanism responsible for this fascia “remodeling”. Disruption of the fascia due to injury or overuse also results in corrupted feedback signals and neurological disorders that are exposing the tissue to additional potential for injury or movement disorders.

Comments

Post a Comment